Julie Bindel's excellent new book

A patriarchal society’s attitude to lesbians is a litmus test

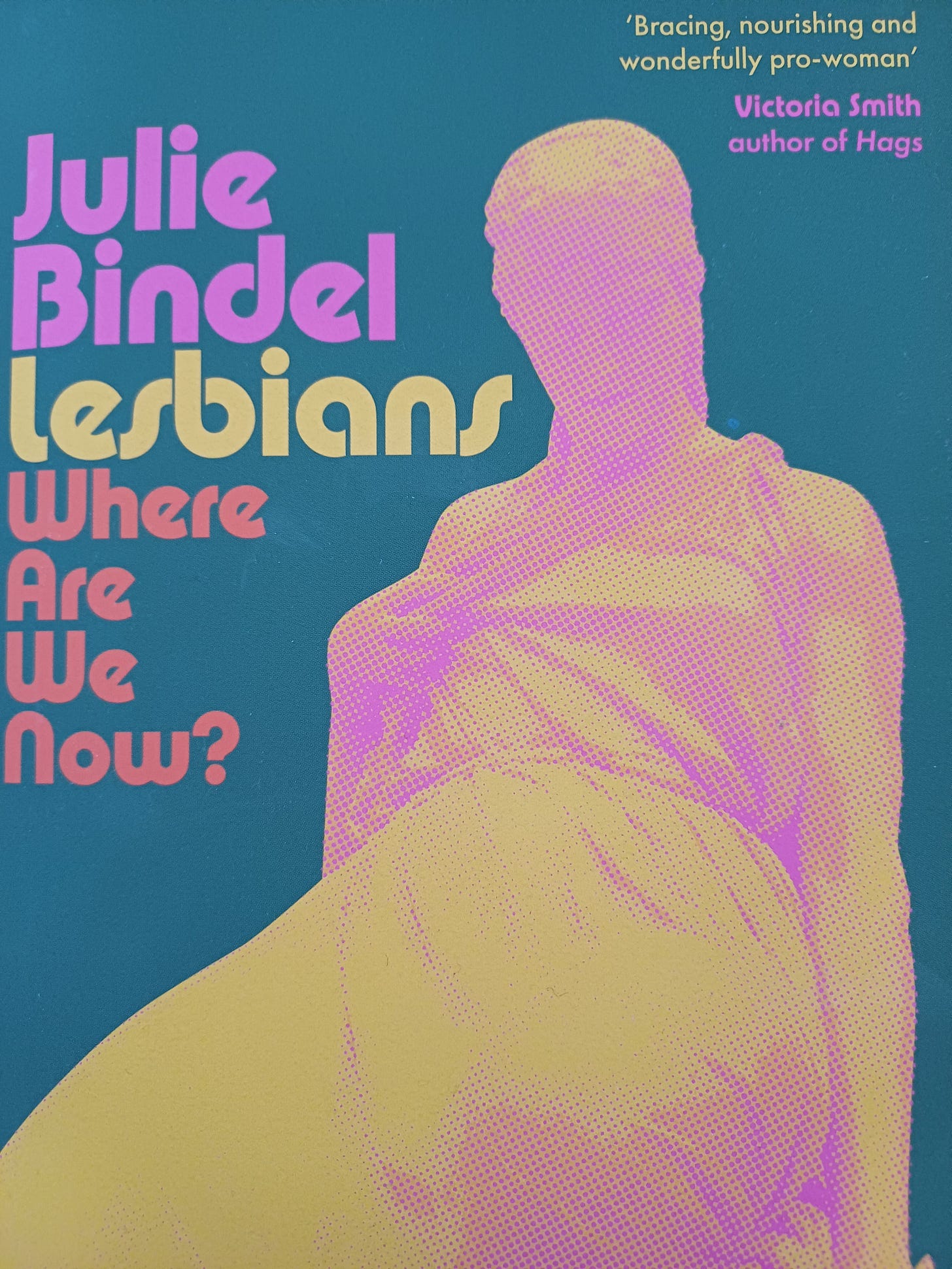

This is my first post and it’s about Julie Bindel’s brand-new book Lesbians: Where Are We Now? I wasn’t planning to start a feminist blog or a book-review blog. But I got a lot out of reading this one, which if I am honest surprised me a bit.

I admired Julie’s earlier book The Pimping of Prostitution very much, and was lucky to be able to edit an extract which ran in the Guardian. But I’m heterosexual and didn’t expect to find so much interest in a book about lesbians. But I did! And I had a few things I wanted to write down after I finished it so here they are…

I interviewed Julie and also Harriet Wistrich in their house when I was researching my own book Sexed: A History of British Feminism (2024). I found talking to them both so rewarding. The story of their campaign on behalf of Emma Humphreys, who was convicted of murdering her violent pimp in 1985, aged just 17, but later released on appeal, is a key element in my chapter about the 1990s.

I think the feminist criminal justice movement of that period - which was one of the outgrowths of the women’s liberation movement - is a hugely important part of the story of UK feminism.

I obviously knew that Julie and Harriet are a couple. Having now read Julie’s book, I think I hadn’t properly grasped before the significance of lesbians in the groups set up to advocate for female victims and survivors of male violence. I am glad to have had this pointed out.

Julie writes in her introduction that the book is “neither a memoir nor a history lesson on lesbians through the ages”. This is true. But it does tell a story about how she arrived at where she is now, as well as making persuasive arguments about lesbian culture and politics.

I was particularly struck by chapter 2, about the centrality of lesbians to the struggle for women’s liberation, which goes beyond the spheres of violence and criminal justice mentioned already. Female bonding is a precondition for feminism, and widely recognised to have a protective function in societies where women have little power and few rights (I have also been reading Sarah Hrdy recently, and evolutionary anthropology supports this idea as well). Sisterhood is solidarity for women and it is an understanding of our shared interests, and the strength of attachments between us, that provide a basis for women’s organising.

For Bindel, there has never been any question that a lesbian life was right for her. “Lesbian culture, friendship networks and relationships are - for the most part - so rewarding, affirming and exhilarating that it’s no wonder some men feel threatened by them and seek to destroy them,” she writes. What I hadn’t fully grasped before is the extent to which a patriarchal culture’s approach to women who reject heterosexuality is a litmus test of its overall attitude to insubordinate women. By prioritising their relationships with each other, lesbians challenge the extent to which a male-dominated society will tolerate feminist dissent.

The book includes a thoughtful section on what being a lesbian is, and acknowledges divergent views between women who are committed to a “born this way” explanation – as some gay men are – and others who take a more flexible view, as Julie does. Becoming a lesbian is a choice, or discovery, that some women make later in life.

There is an interesting discussion of the complex relationship between gay and lesbian activists – who were brought together in the 1980s by Section 28 and the Aids crisis, but also have diverging priorities. For example, some lesbians oppose the libertarian, pro-“kink” strand of male sexual rights activism, and have done for years.

She also sets out what I think is an unarguable case regarding the impact on lesbians of gender identity ideology. Given that lesbian sexuality, by definition, involves women’s avoidance of intimacy with male-sexed people, it is disgraceful that lesbians are vilified for rejecting the claim that by identifying as trans, men can become lesbians.

Julie is of course well known for the forthright position she has taken on this issue. Though she doesn’t recount every instance of this in her book (which isn’t a memoir), she has endured some appallingly rough treatment on account of it. But her clarity regarding the crucial issue of women’s boundaries, and ability to say no to men, does not make her inflexible or dogmatic at all.

She gives one of the most lucid summaries I have come across of feminism’s internal struggle with the categories of sex and gender, and her own recognition of unintended consequences. I agree with her that second-wave feminism played a part in laying the ground for the current repudiation of biology by identity-fixated progressives:

“It was a fundamental tenet of our politics that all things concerning gender were socially constructed - starting with the suffocating rules imposed on both male and female behaviour. But I now wonder if, in our focus on the social construction of gender, we lost sight of sexual difference altogether. So anxious were we to minimise the significance of any biological differences between men and women that we almost ended up ignoring the fact that we inhabited bodies at all.”

I was delighted that my book, Sexed, gets a mention. Julie quotes from Kathleen Stock’s review of it in order to stick up for the consciousness-raising groups of the 1970s. Julie thinks they were important in enabling women to talk to each other in new ways.

Lesbians is an excellent book. Julie is very clear about what she thinks and the book makes a powerful case. Unsurprisingly, I take a more positive view of heterosexuality than she does. But because she makes room for other voices, with interviews threaded through its pages, the overall effect is discursive and engaging.

Lesbians: Where Are We Now? is published by Forum, £20.